The opioid epidemic in the news: Findings from an analysis of Northern California coverage

Wednesday, December 14, 2016More people died in 2014 of opioid overdose than in any other year on record,1 and the epidemic is only worsening. The problem is particularly severe in Northern California, especially in rural communities.2 Key to addressing — and ultimately reversing — this epidemic is understanding the public discourse around it, including how, if at all, solutions appear.

News coverage provides a window into that discourse. In June of 2016, the California Department of Public Health commissioned Berkeley Media Studies Group (BMSG) to monitor print and online news from Northern California about the growing epidemic of opioid abuse and overdose. Below we present the findings of our analysis, which spanned June 27, 2016, through September 30, 2016.

What we did

The news plays a critical role in setting the agenda for public policy debates. Journalists’ decisions about whether and how to cover the pressing problems of the day can raise the profile of an issue and influence how the public and policymakers consider problems and potential solutions. To examine how the news is shaping the discourse around the opioid epidemic, we developed and tested a media search strategy that allowed us to compile and assess print and online news coverage related to prescription opioid abuse and overdose. The search was designed to capture coverage related to a broad range of stories about opioid issues, as well as hyper-local media responses from rural Northern California.

We used a combination of the following three news-tracking tools to monitor opioid coverage using search terms including “opioid,” “opiate,” “overdose,” “fentanyl,” “safe prescribing,” “Narcan/Naloxone” and “doctor shopping”:

Twitter and Real Simple Syndication (RSS) feeds: We established a list of 13 Northern California media outlets based on information from the California Department of Public Health about the highest burden counties and regions of interest. Using the social media tracking tool Hootsuite, we constructed RSS feeds and Twitter alerts for each outlet, filtered through the keywords listed above, to find online media and print media with an online component.

Google news: We augmented our scans of Twitter and RSS feeds with daily news monitoring using Google’s news search service. We limited our results to the Northern California region and searched for coverage containing at least one of the search terms listed above. We also searched for stories outside of Northern California to capture national news about opioids that had relevance to the discourse in Northern California.

Nexis: To ensure representation of hyper-local coverage from rural Northern California, we searched for news articles using the Nexis database. This method allowed us to add articles from the Shasta and Humboldt County regions. However, even with this more advanced strategy, we were unable to access the smallest community papers that serve most remote areas of rural Northern California, since many lacked an online component or social media channel.

After we identified relevant articles, we analyzed them for key information, story elements and themes. We included many of these short analyses in our daily “In the News” newsletter, which is distributed to nearly 400 public health and policy advocates, practitioners and researchers around the country.

What we found

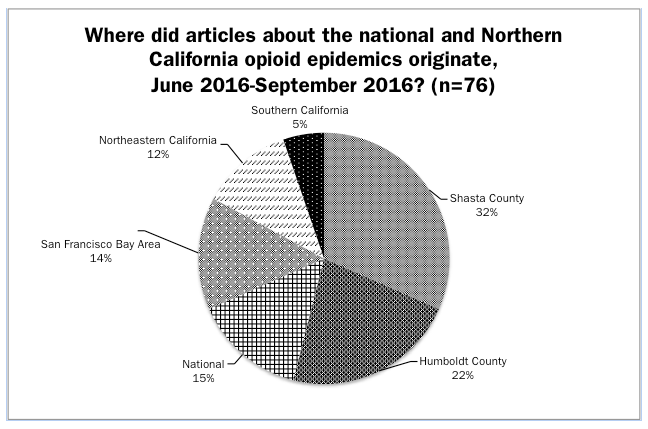

Over the three months of our monitoring, we identified 76 unique news pieces about the opioid epidemic that related either to Northern California or were national stories with implications for the region. Of these articles, 32 percent were specific to Shasta County, 22 percent were articles from Humboldt County and 14 percent were national stories. The remaining articles originated from news sources operating out of the San Francisco Bay Area, Northeastern California and Southern California.

The majority of articles came from Shasta County’s local daily newspaper the Record Searchlight (28 percent) and Humboldt County’s Eureka Times-Standard (18 percent).

In light of the severity of the epidemic in Northern California and the California Department of Public Health’s particular interest in narratives from that area, we include below an in-depth analysis of those articles in particular.

What were stories from rural Northern California about?

When stories about opioids appeared in news coverage from rural Northern California, they focused on hyper-local issues, such as local addiction interventions or rising crime rates resulting from the opioid epidemic. However, almost all provided an overview of the opioid epidemic on a local or national scale and included data or statistics to illustrate the scope of the problem facing their communities. For example, a North Coast Journal piece on falling opioid prescription rates in Humboldt County shares that the “amount of opioids prescribed in the county has dropped by 23 percent since 2010, falling from 1.29 prescriptions per person to 1.14.”3

News from Shasta County

Stories from Shasta County were primarily focused on crimes related to or resulting from the opioid epidemic (42 percent of articles). Of particular local concern were a spate of robberies affecting homeowners and businesses. A Record Searchlight editorial published in mid-July lamented the rise in drug-related crime that led to a local business district’s decision to install a fence around all of its shops: “Redding and Shasta County put their limited resources toward solving a problem that spans the spheres of public health, criminal justice and quality of life. There’s no one easy way to solve the underlying issue — getting people off drugs. Until that’s resolved — or at least brought under control — we must perform triage to keep businesses thriving and help people feel safe.”4

When drug addiction treatment options appeared in the news from Shasta County, they were usually explicitly connected to crime prevention efforts. Redding Police Chief Rob Paoletti was the primary voice in stories about a methadone clinic proposed for the city: “We have to find some solutions to some of these issues and if you look at the majority of the recent robbery suspects we have, they are addicted to heroin,”5 he said in Record Searchlight article.

The remainder of articles from Shasta County focused on matters of state or nationwide concern, such as legislative battles, federal appropriations bills or nationally marketed overdose antidotes such as Narcan.

News from Humboldt County

News coverage from Humboldt County about opioids covered a broader range of topics than did coverage from Shasta County. Typically, stories were in the news due to local efforts to treat addiction or disseminate overdose antidotes. Humboldt County Supervising Mental Health Clinician Sue Grenfell was an active voice in the news, commenting frequently on Humboldt County’s partnership with eight other Northern California counties to create a region-wide drug treatment system. When Grenfell was quoted commenting on the partnership in an article from the Eureka Times-Standard, she framed addiction as a public health rather than a criminal justice issue — an important shift in thinking that appeared again and again in the coverage: “The more we can invest in prevention and treatment, I think the costs will come down for people being incarcerated for a medical condition.”6

Stories from Humboldt County on the use or dissemination of overdose antidotes highlighted specific cases — most notably the life-saving efforts of local librarian Kitty Yancheff, who used an overdose kit provided by the Humboldt County Department of Health and Human Services to save an overdosing patron’s life.

Other features of the news from rural Northern California

Part of solving a problem is identifying who is responsible for solving it. County and police department representatives were prominent in the news about opioid addiction in rural Northern California, but opioid addiction in the news was frequently framed as a medical or public health issue. Consequently, we wanted to know how doctors and medical professionals appeared in the coverage. We found that only a small number of articles from both Shasta and Humboldt Counties mentioned the role of doctors in addressing the opioid crisis. When doctors did appear in the coverage, it was usually because of California Senate Bill 482, a bill signed into law this September that seeks to curb “doctor shopping,” the practice of visiting multiple doctors to obtain multiple prescriptions for illegal drugs, by requiring doctors to consult a database before prescribing opioids.

Conclusion

The news in rural Northern California and elsewhere in the country provides a window through which we can glimpse how the public — and policymakers — understand the critical epidemic of opioid abuse and overdose in the region. Our preliminary analysis found that the news reinforces that the opioid epidemic is severely affecting communities locally and nationally; that the epidemic drives local crime; and that communities are exploring fledgling prevention and recovery efforts. Unlike previous responses to drug use, opioid addiction is routinely framed in the news as a public health issue as well as a criminal justice issue — but public health advocates and medical practitioners are largely absent from the coverage.

Our findings lay the groundwork for additional research questions, such as: What are the opportunities for public health and medical professionals to become part of the narrative around opioid abuse and overdose? What narratives are emerging in the most rural parts of Northern California? Who should be part of the public discussion around this issue, and how can those working to end opioid abuse engage with them? The answers to these and other questions will help us understand the challenges and opportunities in the discourse about the opioid epidemic — and what they mean for all those working to end opioid addiction and abuse in Northern California and beyond.

Acknowledgments

This report was written by Lillian Seklir; Pamela Mejia, MS, MPH; and Lori Dorfman, DrPH.

This work was funded by the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) and was supported by Grant Number 6NU17 CE002747, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Department of Health and Human Services, or CDPH.

Thanks especially to the CDPH Prescription Drug Overdose Prevention Initiative for providing expert insight, guidance and feedback.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015, December 18). Drug overdose deaths hit record numbers in 2014. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2015/p1218-drug-overdose.html. Accessed October 13, 2016.

2. Reese P. (January 22, 2016). Two maps illustrate California’s growing opioid epidemic. The Sacramento Bee.

3. Greenson T. Opioid Prescription Rates Falling in Humboldt. Available at: http://www.northcoastjournal.com/NewsBlog/archives/2016/09/14/opioid-prescription-rates-falling-in-humboldt.

4. Sad state of affairs when businesses want a fence. (July 15, 2016). The Record Searchlight, Editorials.

5. Longoria S. (August 11, 2016). Paoletti pushes methadone clinic to help curb drug-fueled crime. The Record Searchlight.

6. Houston W. (August 13, 2016). Trageting the OD epidemic: Counties to create regional treatment system. The Eureka Times Standard.